A few years back, I reviewed Jonathan Green’s Unnatural History, the first in Abaddon Books’ Pax Britannia series. I had just finished Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day and needed lighter fare. Based on Mark Harrison’s cool cover art, I had high hopes for the Pax Britannia series, especially Leviathan Rising. I took the first two on vacation as potential beach reading. To my chagrin, Unnatural History was nigh unreadable, due largely to writing style and the lead character, Ulysses Quicksilver, with all the ruthless and rakish behavior of a steampunk James Bond, but none of the charm. On the upside, I found the second book in the series, Al Ewing’s El Sombra, much better, fulfilling my penny-dreadful/pulp fiction expectations without requiring me to ignore style and grammar. Having sampled the series, I moved on to other steampunk, promising myself I’d return to reading the remaining novels I’d purchased.

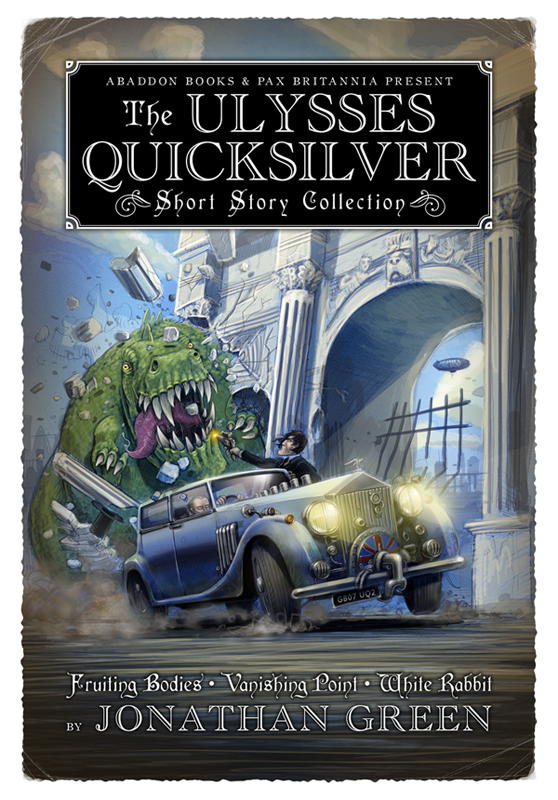

Two years later, I’m staring down the barrel of another summer vacation, pondering my reading choices. Enter The Ulysses Quicksilver Short Story Collection as ebook, reprinting three short works originally published in early Pax Britannia novels.

That I can make the distinction of early novels is noteworthy. Despite my low opinion of Unnatural History, Green has gone on to publish six sequels. Clearly, this series deserves another look, even if only to ascertain whether I was just in a foul mood when I read Unnatural History.

If you’re unfamiliar with the premise of Pax Britannia, it’s ludicrous but simple: Queen Victoria’s reign has persisted into the 1990s, along with Hitler’s Third Reich. While any serious student of history and culture will roll their eyes at this, it’s best to ignore how batshit improbable this premise is and let the fun ensue. Otherwise, you’ll be saying things like, “What the hell do they need a horse and cart for? They have high speed vehicles!” or “Seriously? The waistcoat and cravat are still in style?” From where I’m sitting, Green is going for an “ain’t it cool?” factor, not a “is it counterfactually probable?” one.

With such an attitude in mind, I enjoyed Green’s writing more with this collection. I have yet to finish another of Green’s novels, but I can recommend these short stories as fun, light reading, and as digital media, physically light as well. In short, it’s exactly the sort of thing you want to take on a summer vacation when you want to get away from heavy reading.

The first story, “Fruiting Bodies,” was originally released as an extra at the end of El Sombra. As I was still loathing Green’s writing at the time, I didn’t bother giving it a look. I’d really enjoyed El Sombra, and recommend it for anyone who appreciates shirtless Zorroesque heroes going toe-to-toe with Nazis in rocketpacks and their steam warbot. It’s Batman meets Desperado meets Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow meets Inglorious Basterds. But I digress.

“Fruiting Bodies” is the weakest of the collection, but it’s still a good deal of fun if you can check your brain at the door. I still found Ulysses Quicksilver a difficult protagonist to love, but as a cad, he couldn’t care less what anyone thinks of him, least of all some academic from the Colonies. I dialed my brain down to Clive Cussler level, and although the Quicksilver of “Fruiting Bodies” still lacks the charm of a Dirk Pitt, I found him less grating. The storyline involves a violently aggressive plant species sprouting up in corpses around London, and Quicksilver’s race to find out what’s behind it. That’s the formula of the Ulysses Quicksilver short stories—a steampunk Scooby Doo with a Queen’s Agent instead of German shepherd, a cool-headed butler instead of Shaggy, and a kick-ass Rolls Royce called the Silver Phantom instead of the Mystery Mobile.

Quicksilver finally finds his charm in “Vanishing Point,” where the mystery surrounds the appearance of a phantom apparition at a séance put on by a con artist. It’s a standard plot device in steampunk books involving séances: the idea of spiritualism as fraudulent is well established, so that when a real ghost appears, as in Mark Frost’s The List of Seven and Mark Hodder’s The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man, it’s clear that “something strange is going on.” Savvy readers of speculative fiction may guess the ending before reading it, but this suggests a possible intended reader for the Pax Britannia series. The books are reminiscent of the sort of writing I ploughed through as a voracious reader in my teens: the numerous Conan pastiches, Don Pendleton’s Executioner series, and Doc Savage reprints. It isn’t high literature, it’s highly formulaic, and there’s little that’s exceedingly original. It’s the literary equivalent of junk food, nourishment best consumed in our teen years when our metabolisms haven’t left the building. Furthermore, younger readers are less exposed to what older readers find formulaic or cliché. Accordingly, these short stories are best recommended for younger readers who want slightly edgier steampunk reading than Scott Westerfeld or Arthur Slade are providing (or in the case of El Sombra, significantly edgier steampunk reading). Likewise, anyone looking for a return to “science fiction’s age thirteen,” as Paul De Filippo calls steampunk in Steampunk Prime, will likely enjoy Ulysses Quicksilver’s adventures.

Finally, we come to “White Rabbit,” the best of the offerings in the collection, and a clear indication of Green’s progress as a writer. The story alludes to pop culture references Green is fond of sprinkling through his stories, such as the line “we can rebuild her—we have the technology,” spoken of the dying Queen Victoria a steampunk bionic woman, as the reference implies. It also contains a shameless plug for all the Pax Britannia stories to its publishing date in the back of Blood Royal, the fifth Pax Britannia novel by Green. If you’re in for a penny with the series at this point, this dreamt flashback sequence will put you in for a pound: exploding airships, sword battles with scaled monstrosities, werewolves, and nautical disasters. But Quicksilver wakes from his dream to an unexpected environment: a lunatic asylum. And in this moment, I found Green had finally struck the balance between his series preposterous premise and the ironic voice that would permit us to enjoy it without feeling the need to take it too seriously: “He stared forlornly at the seat-less lavatory bolted to the wall and couldn’t help feeling that something had gone horribly wrong.” Green continues this voice, one of the keys to Gail Carriger’s Parasol Protectorate series upon the introduction of characters from Alice in Wonderland. As Quicksilver finds himself in danger, he wonders, “Where was a rabbit in a waistcoat to direct you when you needed one?” With references to blue pills and rabbit holes, savvy readers will again be thinking in the right direction long before Green shows his hand, but unlike “Vanishing Point,” it takes a greater deal of attention to guess the source behind the problem involved in this story of virtual reality and insanity wrapped up as a recursive fantasy involving Alice in Wonderland.

While I owned two of these stories, I was glad for the convenience of carrying them on my iPhone’s Kindle app. For those looking for a fun summer reader that will neither demand you parse history, or at the exceeding deal of 99 cents on Amazon, break the bank, look no further than The Ulysses Quicksilver Short Story Collection. At that price, a Canadian might call it a Loonie Dreadful, and contrary to my expectations, well worth the price.

NOTE: While perusing my copies of Pax Britannia books to see what other short works were included in the back, I came across Green’s “Christmas Past,” which joins J. Daniel Sawyer’s “Cold Duty” in the small minority of steampunk Christmas tales. I’m looking forward to reviewing it come the Yuletide season this year.

Mike Perschon is a hypercreative scholar, musician, writer, and artist, a doctoral student at the University of Alberta, and on the English faculty at Grant MacEwan University.